Người đầu tiên giới thiệu cho mình về hệ thống thần Nat của đất nước Miến Điện, chính là anh Sao người Miến Điện, vào khoảng năm 2001. Hồi đó, anh Sao cùng mình đều là học trò thầy Daniel (zemi Daniel).

Sau rồi, có thêm mấy người bạn Miến Điện nữa ở trong và ngoài phòng 404 (cùng trong phòng 404 thì đều thuộc quân AA-ken thuộc Togaidai). Câu chuyện về bộ thần Nat càng thêm thấy thú vị qua lời kể và tư liệu của các bạn ấy.

Đại khái khởi đầu là vậy.

Bây giờ, đi một ít bài nhanh về Nat. Mở đầu là một bản dịch của bạn Tây Nguyên Xanh. Bổ sung và cập nhật thì được dán dần lên ở bên dưới đó.

Tháng 2 năm 2023,

Giao Blog

---

Bình Dương, 05/10/2022

Biên dịch: Tây Nguyên Xanh

Nội dung được dịch từ bài viết trên blog của Inside Asia đăng ngày 02/02/2017

https://vunglep.blogspot.com/2022/10/tin-nguong-tho-cac-vi-than-nat-cua-mien.html

..

---

BỔ SUNG

2.

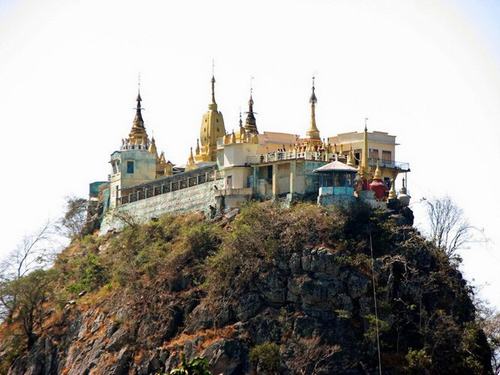

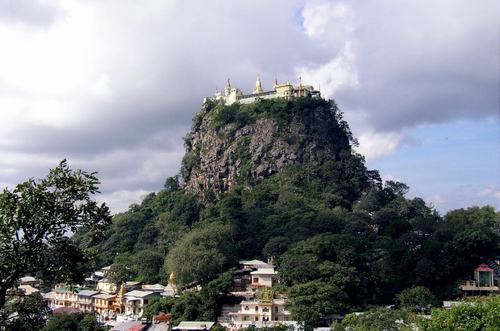

Tu viện trên núi độc đáo nhất thế giới

(Xây dựng) - Tu viện Taung Kalat tọa lạc trên ngọn núi Taung Ma-gyi của Miến Điện hay Myanmar. Nơi đây thờ 37 vị thần huyền thoại và thu hút lượng du khách rất lớn đến thăm quan hằng năm bởi vẻ đẹp có một không hai trên thế giới.

Taung Kalat được làm trên đỉnh của một ngọn núi đá phun trào bị bít kín miệng núi lửa hiện đã tắt. Đôi khi Taung Kalat cũng được gọi là núi Popa và người dân địa phương gọi là Taung Ma-gyi, nghĩa là “đồi mẹ”.

Du khách đến hành hương Taung Kalat sẽ phải dũng cảm leo lên 777 bậc thang để được chiêm ngưỡng toàn cảnh bao quanh. Người hành hương đến đây luôn tin rằng cách ngọn Taung Ma-gyi không xa là nơi sinh sống của các vị thần Nat và 37 vị thần Nat đóng vai trò quan trọng trong thời gian tồn tại của đất nước chùa tháp.

Câu chuyện cuộc đời của các Nat có lẽ là những huyền thoại kỳ bí đối với hầu hết du khách. Mặc dù tất cả 37 vị Nat được thờ trên Taung Ma-gyi nhưng chỉ có 4 thần còn tồn tại ở nơi này. Đó là Maung Tint Dai, Saw Me Yar, Byatta và Mai Wunna. Và mỗi vị thần có một câu chuyện kỳ bí riêng khiến cho du khách không khỏi sững sờ. Thần Nat còn là một nhóm các vị thần đóng vai trò bảo hộ cho con người và là linh hồn của núi rừng.

Một điều nữa mà nơi đây thu hút đông khách thập phương đến hành hương còn bởi việc xây dựng một tu viện độc đáo trên những vách núi đá thẳng đứng vẫn là một câu chuyện bí ẩn của người Miến Điện cổ xưa.

Hạ Ly (Tổng hợp)

https://baoxaydung.com.vn/tu-vien-tren-nui-doc-dao-nhat-the-gioi-172373.html

1.

Nat (deity)

The nats (နတ်; MLCTS: nat; IPA: [naʔ]) are god-like spirits venerated in Myanmar and neighbouring countries in conjunction with Buddhism. They are divided between the 37 Great Nats who were designated that status by King Anawrahta when he formalized the official list of nats. Most of the 37 Great Nats were human beings who met violent deaths.

There are two types of nats in Burmese Belief: nat sein (နတ်စိမ်း) which are humans that were deified after their deaths and all the other nats which are spirits of nature (spirits of water, trees etc.).

Much like sainthood, nats can be designated for a variety of reasons, including those only known in certain regions in Burma. Nat worship is less common in urban areas than in rural areas and is practised among ethnic minorities of Myanmar as well as in mainstream Bamar society. However, it is among the Theravada Buddhist Bamar that the most highly developed form of ceremony and ritual is seen.[1]

Every Burmese village has a nat kun (နတ်ကွန်း) or nat sin (နတ်စင်) which essentially serves as a shrine to the village guardian nat called the ywa saung nat (ရွာစောင့်နတ်). Individual houses also have a shrine to a nat, usually a coconut is hung on a corner of the house or property, surrounded by perfume as an offering. One may inherit a certain member or in some instances two of the 37 Great Nats as mi hsaing hpa hsaing (မိဆိုင်ဖဆိုင်; lit. 'mother's side, father's side') from one or both parents' side to worship depending on where their families originally come from. One also has a personal guardian deity called ko saung nat (ကိုယ်စောင့်နတ်).[2]

Nat worship and Buddhism[edit]

Academic opinions vary as to whether Burmese Buddhism and Burmese spirit worship are two separate entities, or merged into a single religion.[citation needed] As with a rise of globalization, the importance of the nat religion on modern Myanmar and its people has been diminished. The formalizing of the official 37 Great Nats by King Anawrahta (1044–1077) of Bagan, has been interpreted as Burmanisation and establishment of Bamar supremacy in the Irrawaddy valley after the unification of the country and founding of the First Burmese Empire.[1] Worship of nats predates Buddhism in Burma. With the arrival of Buddhism, however, the nats were syncretically merged with Buddhism.[citation needed]

Nat worship and ecology[edit]

The widespread traditional belief among rural folks that there are forest guardian spirits called taw saung nats (တောစောင့်နတ်) and mountain guardian spirits called taung saung nats (တောင်စောင့်နတ်) appears to act as a deterrent against environmental destruction up to a point. Indiscriminate felling particularly of large trees is generally eschewed owing to the belief that they are dwellings of tree spirits called yokkazo (ရုက္ခစိုး; tree spirit) and that such an act would bring the wrath of the nat upon the perpetrator.[3]

Popular nat festivals[edit]

The most important nat pilgrimage site in Burma is Mount Popa, an extinct volcano with numerous temples and relic sites atop a mountain 1300 metres tall located near Bagan in central Burma. The annual festival is held on the full moon of the month of Natdaw (December) of the Burmese calendar.[4] Taungbyone, north of Mandalay in Madaya Township, is another major site with the festival held each year starting on the eleventh waxing day and including the full moon in the month Wagaung (August).[5] Yadanagu at Amarapura, held a week later in honour of Popa Medaw ("Mother of Popa"), who was the mother of the Taungbyone Min Nyinaung ("Brother Lords"), is also a popular nat festival.[2]

Nats are ascribed human characteristics, wants, and needs; they are flawed, having desires considered derogatory and immoral in mainstream Buddhism. During a nat pwè, which is a festival during which nats are propitiated, nat kadaws (နတ်ကတော် "wife of the spirit",[6] i.e. "medium, shaman") dance and embody the nats. Historically, the nat kadaw profession was hereditary and passed from mother to daughter. Until the 1980s, few nat gadaws were male. Since the 1980s, persons identified by outsiders as trans women have increasingly performed these roles.[6]

Music, often accompanied by a hsaing waing ("orchestra"), adds much to the mood of the nat pwè, and many are entranced. People come from far to take part in the festivities in various shrines called nat kun or nat naan, get drunk on palm wine and dance wildly in fits of ecstasy to the wild beat of the Hsaing waing music, possessed by the nats.[4]

Whereas nat pwès are annual events celebrating a particular member of the 37 Great Nats regarded as the tutelary spirit in a local region within a local community, with familial custodians of the place and tradition and with royal sponsorship in ancient times, hence evocative of royal rituals, there are also nat kannah pwès where individuals would have a pavilion set up in a neighbourhood and the ritual is generally linked to the entire pantheon of nats. The nat kadaws as an independent profession made their appearance in the latter half of the 19th century as spirit mediums, and nat kannahs are more of an urban phenomenon which evolved to satisfy the need of people who had migrated from the countryside to towns and cities but who wished to carry on their traditions or yo-ya of supplicating the mi hsaing hpa hsaing tutelary deities of their native place.[1]

List of official nats[edit]

King Anawrahta of Bagan (1044–1077) designated an official pantheon of 37 Great Nats after he had failed to enforce a ban on nat worship. His stratagem of incorporation eventually succeeded by bringing nats to Shwezigon Pagoda portrayed worshipping Gautama Buddha and by enlisting Śakra, a Buddhist protective deity, to head the pantheon above the Mahagiri nats as Thagyamin.[4][7] Seven out of the 37 Great Nats appear to be directly associated with the life and times of Anawrahta.[7]

The official pantheon is made up predominantly of those from the royal houses of Burmese history, but also contains nats of Thai (Yun Bayin) and Shan (Maung Po Tu) descent; illustrations of them show them in Burmese royal dress. Listed in proper order, they are:

- Thagyamin (သိကြားမင်း)

- Min Mahagiri (မင်းမဟာဂီရိ)

- Hnamadawgyi (နှမတော်ကြီး)

- Shwe Nabay (ရွှေနံဘေး)

- Thonbanhla (သုံးပန်လှ)

- Taungoo Mingaung (တောင်ငူမင်းခေါင်)

- Mintara (မင်းတရား)

- Thandawgan (သံတော်ခံ)

- Shwe Nawrahta (ရွှေနော်ရထာ)

- Aungzwamagyi (အောင်စွာမကြီး)

- Ngazi Shin (ငါးစီးရှင်)

- Aung Pinle Hsinbyushin (အောင်ပင်လယ်ဆင်ဖြူရှင်)

- Taungmagyi (တောင်မကြီး)

- Maungminshin (မောင်မင်းရှင်)

- Shindaw (ရှင်တော်)

- Nyaunggyin (ညောင်ချင်း)

- Tabinshwehti (တပင်ရွှေထီး)

- Minye Aungdin (မင်းရဲအောင်တင်)

- Shwe Sitthin (ရွှေစစ်သင်)

- Medaw Shwezaga (မယ်တော်ရွှေစကား)

- Maung Po Tu (မောင်ဘိုးတူ)

- Yun Bayin (ယွန်းဘုရင်)

- Maung Minbyu (မောင်မင်းဖြူ)

- Mandalay Bodaw (မန္တလေးဘိုးတော်)

- Shwe Hpyin Naungdaw (ရွှေဖျင်း နောင်တော်)

- Shwe Hpyin Nyidaw (ရွှေဖျင်း ညီတော်)

- Mintha Maungshin (မင်းသား မောင်ရှင်)

- Htibyuhsaung (ထီးဖြူဆောင်း)

- Htibyuhsaung Medaw (ထီးဖြူဆောင်း မယ်တော်)

- Pareinma Shin Mingaung (ပရိမ္မရှင် မင်းခေါင်)

- Min Sithu (မင်းစည်သူ)

- Min Kyawzwa (မင်းကျော်စွာ)

- Myaukhpet Shinma (မြောက်ဘက်ရှင်မ)

- Anauk Mibaya (အနောက် မိဘုရား)

- Shingon (ရှင်ကုန်း)

- Shingwa (ရှင်ကွ)

- Shin Nemi (ရှင်နဲမိ)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Brac de la Perriere, Benedicte. "The Spirit-possession Cult in the Burmese Religion" (PDF). dhammaweb.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-03-04. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ a b Spiro, Melford (1996). Burmese Supernaturalism. Transaction Publishers. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-4128-1901-5.

- ^ Dr Sein Tu. "Traditional Myanmar Folk Beliefs and Forest and Wildlife Conservation". Perspective (January 1999). Retrieved 2008-09-13.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Maung Htin Aung (February 1958). "Folk-Elements in Burmese Buddhism". The Atlantic Monthly. Archived from the original on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ Shwe Mann Maung. "The Taung Byone Nat Festival". Perspective (August 1997). Archived from the original on 2004-07-17. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ a b Ho, Tamara C.; Discourse (Fall 2009). "Transgender, Transgression, and Translation: A Cartography of Nat Kadaws". Discourse. 31 (3): 273–317.

- ^ a b DeCaroli, Robert (2004). Haunting the Buddha: Indian Popular Religions and the Formation of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0-19-516838-9. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- 'King Mae Ku: From Lan Na Monarch to Burmese Nat', in: Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 1. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012.

- Salek, Kira (May 2006). "Myanmar's River of Spirits". National Geographic Magazine. pp. 136–157.

- U Kyaw Tun; et al. (2005-01-15). "Nat in My Classroom!". Tun Institute of Learning. Archived from the original on 2012-12-03. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- Temple, R.C. (1906). The Thirty-seven Nats-A Phase of Spirit-Worship prevailing in Burma.

- Hla Tha Mein

External links[edit]

- "Images of the 37 nats". NYPL Digital Gallery.

- Nat belief and Buddhism Photo essay by Claudia Wiens

- The Nats - Online Burma/Myanmar Library

- Friends in High Places Preview of a documentary film by Lindsey Merrison

- Nat Dance YouTube

- Mintha Theater Dance theater in Mandalay, Burma.

- Spirit of Burma 2006

- Nat Pwè recordings

- The Nat Spirits and Burmese Animism Windows on Asia, Michigan State University

- Myanmar Cyclone Brings Rise in Centuries-Old 'Nat' Worship The Wall Street Journal, June 30, 2008, video and photo slideshows

- Festival brings noise and colour to Taungbyone Zaw Win Than, The Myanmar Times Vol. 22 No. 430, August 4–10, 2008

- Myanmar Nat Pwe in Bago Flickr photos by Boonlong1

- My House Nat Can Whip Your House Nat Ethan Todras-Whitehill, Student Traveler, 2006-11-24

- An account of the Taungbyone 2010 nat pwe spirit festival at Arcane Candy Part 1 and Part 2

- Myanmar's River of Spirits Kira Salak, National Geographic. May 2006

- The Thirty Seven Nats. A Phase of Spirit-Worship prevailing in Burma | Southeast Asia Digital Library

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nat_(deity)

..

ナッ信仰

ナッ信仰(ナッしんこう、ビルマ語: နတ်、IPA: /naʔ/; Nat)は、ミャンマーの民間信仰・土着信仰である。「ナッ」は、精霊、魔神、死霊、祖霊などを表す言葉である。ミャンマーにおいては仏教と並存し、混成の民間信仰を形成している[1]。カチン族、カレン族、シャン族、モン族の間にもナッ信仰と類似するアニミズムが存在する[1]。

歴史[編集]

信仰の歴史は古く、ビルマ族が同地に王国を形成する以前から存在した。

11世紀にパガン王朝を建国したアノーヤターは各地で信仰されているナッを37柱のパンテオンにまとめ、仏教の守護神であるダジャーミン(ビルマ語: သိကြားမင်း)の下に他のナッを配して仏教の優位性を表した[2]。ナッ信仰の確立には政治的意図が介入し、タトゥン、バガン(パガン)近郊のポウパー山、マンダレー近郊のタウンビョン、シャン高原などのビルマの歴代王朝が重要視した土地がナッ信仰の聖地とされている[3]。ナッの世界の構造はビルマの政治体制に基づくものとなっており、ナッと人間の従属関係はビルマの伝統的な地方支配者と領民の関係に対応しており、政治支配の基盤が領土内の世帯に置かれているように各戸にマハーギーリーが祀られている[4]。人々は祈願成就のためにナッに供え物を奉げる一方で、ナッがもたらす災厄を恐れているが、こうした関係は民衆と政治権力の関係に重ねられる[5]。

ポッパ山は家の守護神であるマハーギーリー(ビルマ語: မဟာဂီရိ)の住処として信仰を集め、ビルマ暦のナドー月(ビルマ語: နတ်တော်)と新年の2回ナップエ(祭礼、精霊儀礼)が行われる。マンダレーの北に位置するタウンビョン村(ビルマ語: တောင်ပြုံးရွာ、IPA: /tàʊmbjóʷN jwà/)はアノーヤターに仕えた二人の兄弟ゆかりの聖地として知られている[6]。タウンビョンでは二兄弟の伝説に由来する祭礼が開かれ、村と周囲には二兄弟と彼らに関係する人間にまつわるパゴダ、祠が建てられている。

ナッの性質[編集]

ナッは人間の目に映らない存在だとされている[7]。ナッは人間の守護霊でありながら、人々が供え物を怠り禁忌を犯した場合には災厄をもたらし、時には気分次第で不幸を呼び寄せる存在として畏怖されている[5]。ナッの種類には家屋や村落の守護霊のほか、親から継承するものも存在する。ナッが支配下に置いている人間から供え物を受け取る関係はサインと呼ばれ、前の世代の人間が結んでいたサインの関係はヨウヤーナッ(ビルマ語: ရိုးရာနတ်、IPA: /jójà naʔ/; 血筋によるナッ)として子孫に継承される[4]。

ナッの神格は自然物に宿るものから擬人化されて個性を与えられたものまで多岐にわたり[8]、非業の死を遂げた人物の中にはナッとして祀られた者が多い[9]。権力者への反逆の結果非業の死を遂げた人物の伝説を祭礼で再現することは支配権力への反抗の結果を人々に知らしめるとともに、反抗の象徴的表現を認めることで権力者や支配への不満を和らげる効果もあった[10]。

ミャンマーの寺院には多くのナッの像が置かれており、中でも37柱のナッが重要視されている[1]。初期のナッのパンテオンには36柱のナッの頂点にマハーギーリーが置かれていたが、36という数字は世界を4、もしくは4の倍数に分割するヒンドゥー教・仏教の世界観に基づくと言われている[11]。アノーヤターは仏教の帝釈天・ヒンドゥー教のインドラに相当するダジャーミンを36のナッの上に置いてナッ信仰が仏教の下位にあることを示した上で信仰を認め、37柱のナッの像をシュエズィーゴン・パゴダに置き、ナッが仏教を守護する存在であることを表した[11]。パンテオンを構成する37柱のナッは時代・地域・ナッのリストを編纂する人間によって異なり[12]、37柱のナッのリストの編纂は王朝時代から続けられている[9]。1820年にコンバウン王朝の宮廷で作成されたリストのナッはダジャーミンを除いて全て非業の死を遂げた人間の死霊で、うち15体はアヴァ王朝、タウングー王朝の人物だった[13]。16世紀までは37柱に含まれるナッの交代がたびたび行われていたが、王権の介入が強まる17世紀以降、新規のナッが37柱に編入される現象は見られなくなる[14]。

家の守護神であるマハーギーリーは、王によって火刑に処されたタガウン王国の鍛冶屋と彼の後を追って火に飛び込んだ妹の精霊であり、パガン王アノーヤターによって土着のナッの頂点に据えられた[2]。パガン王朝の成立前にはエインサウン・ナッというナッが家の守護神とされていたが、アノーヤターによる宗教改革によってマハーギーリーが各家庭で祀られるようになった結果、二つの神は同一視されるようになったと言われている[15]。家の南東の柱には赤い布を被せたココヤシが吊り下げられていることがあるが、これは家のナッへの供え物、家のナッの住処、家のナッの象徴を兼ねている[16]。家内のナッを祀る棚は仏陀を祀る棚の下に置かれるが、これはミャンマーでは仏教がナッ信仰の上位に置かれているためである[8]。

村の守護神であるイワソーン・ナッは村の外れで祀られ、穀物の神ナジーと土地神ブマディは収穫の直前に行われる祭りの主神とされている。村の守護神の支配領域は村落内に限られており、ミャンマーの人間は遠出をする時には自分の土地のナッを鎮撫するためにフトモモの木の枝を乗り物に括り付けることがある[17]。田植えの時期には田のナッと土地のナッに供え物が奉げられ、雨乞いの時には雨のナッ(テイン・ナッ)を興奮させるために綱引きが行われる。

ナッと人間の関係[編集]

ナッ信仰の信者の中には富裕層、高学歴者、社会的地位の高い人間も見られ、仏教徒だけでなくキリスト教徒やイスラム教徒の中にもナッを信仰する人間がいる[18]。一方でナッは一種の前近代性の象徴と見なされることもあり、都市部の知識人の中には家の守護霊のナッを祀らないものも多い[10]。また、信じているとも信じていないとも断言できないと言う人もいる[7]。ミャンマーにおいては日常生活でナッの話題が出ることは多くなく、ナッの種類や名称、人間とナッの位置づけについて詳細な知識を持った人間も少ないと言われ、霊的存在全般を語るときに「ナッ」の言葉が使われることが多い[7]。ナッ信仰に消極的な人間が多い理由として、保守的かつ敬虔な仏教徒はブッダを除いた超自然的存在であるナッを敬遠し、狂騒的な祭礼を忌避することなどが挙げられている[19]。仏教的な世界観では涅槃に到達する近さは僧侶、男性、ナッ、女性の順であり、男性は位の低いナッに関わるべきではないとされ、祠に供え物をするのは女性の役割となっている[19]。

命名式、結婚式、葬式などの非仏教的なビルマ土着の風習を起源とする通過儀礼では、当事者のナッ(コーサウン・ナッ、あるいはミザイン・パザイン・ナッと呼ばれる)が供養される[20]。

ナッを祀る祭礼であるナップエ(ビルマ語: နတ်ပွဲ、IPA: /naʔpwɛ́/ ナップウェー)は、ミャンマー各地から多くの信者やナッカドーが集まるものから、家の守護霊を祀る棚の壺に草花を奉げるものまで様々な規模のものがある[8]。豊作祈願、旅行安全が伝統的なナップエの目的だが、都市部では病根退散、商売繁盛といった現世利益を追求するナップエも開催されている[9]。農村部の祭礼は小規模で簡素なものである一方都市部では熱狂的な祭礼が開かれており[21]、ナッ信仰の聖地のひとつタウンビョンで行われるナップエはミャンマーで最大の規模を有する[9]。個人の依頼によって行われるナップエは民家の軒先に建てられた仮小屋や町の建物の一階部分で開かれる。建物の奥にはいくつものナッの像が並べられ、サインワイン(ビルマ語: ဆိုင်းဝိုင်း)と呼ばれる伝統的なビルマ音楽が鳴らされる中でナッカドーと呼ばれる霊媒者が踊り続ける。時には信者や見物人も踊りに参加し、踊りの合間には札束がばらまかれる[22]。ばらまく札束の金額が多いほどより多くの利益が得られると考えられており、ばらまかれた紙幣は縁起物と見なされている[23]。祈祷によって願望が成就した際には、供え物やナップエの開催などのナッへの相応の返礼が求められる[24]。こうした点から、ナップエは経済的に成功した人間の利益の再分配、人間関係の構築といった役割を持っていることが指摘されている[23]。

ナップエにおいてはナッカドー(ビルマ語: နတ်ကတော်、IPA: /naʔɡədɔ̀/ ナッガドー;「ナッの妻」の意)と呼ばれる踊り手が人間とナッの仲介役を果たし、普段都市部に住む職業的ナッカドーたちは顧客が開く祭礼に参加する。職業的ナッカドーの有力な顧客には役人・軍人・商人の妻や俳優、踊り手が多いと言われ、彼らは夫の無事や昇進、自らの出世を祈願する[25]。ナッカドーにはメインマシャー(ビルマ語: မိန်းမလျာ、IPA: /méʲmma̰ɕà/)と呼ばれる「ニューハーフ」に相当する人々が多い[8]。一人前のナッカドーになるには他のナッカドーに弟子入りして踊りを習得した後、特定のナッと結婚式を挙げなければならないとされている[26]。祭礼の中でナッカドーは瓶の中の酒を飲み干し、あるいは煙草を吸いながら踊り、興奮が高まると口の中にロウソクの火を入れることもある[22]。ナッカドーが踊っている間、彼らの中にナッが入り込んだ状態になり、信者は踊りの合間にナッカドーの中のナッに相談を持ちかける[22]。ナッカドーはナッオウッと呼ばれる祭礼の先導役によって統率され、ナッオウッは祭礼の場以外でもナッカドーに影響力を行使する[27]。

脚注[編集]

- ^ a b c 太田「ナッ信仰」『アジア歴史事典』7巻、197頁

- ^ a b 田村、松田『ミャンマーを知るための60章』、18-21頁

- ^ 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、118-120頁

- ^ a b 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、120頁

- ^ a b 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、123頁

- ^ 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、115-116頁

- ^ a b c 山本文子「精霊の実在をめぐる不確定性と非実在性の研究のための一考察 : ビルマのナッ信仰の場合」『年報人間科学』第30号、大阪大学人間科学部社会学・人間学・人類学研究室、2009年、 119-135 (p.120-122)、 doi:10.18910/12650、 ISSN 0286-5149、 NAID 120004846834。

- ^ a b c d 田村、松田『ミャンマーを知るための60章』、198-200頁

- ^ a b c d 高谷「ナッ信仰」『新版 東南アジアを知る事典』、310-311頁

- ^ a b 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、121頁

- ^ a b 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、118頁

- ^ 田村、根本『ビルマ』、207頁

- ^ 大野、桐生、斎藤『ビルマ』、67-68頁

- ^ 大野、桐生、斎藤『ビルマ』、68頁

- ^ 大野、桐生、斎藤『ビルマ』、61頁

- ^ 大野、桐生、斎藤『ビルマ』、59頁

- ^ 大野、桐生、斎藤『ビルマ』、65頁

- ^ 田村、根本『ビルマ』、205-206頁

- ^ a b 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、122頁

- ^ 大野、桐生、斎藤『ビルマ』、51,62頁

- ^ 田村、根本『ビルマ』、205頁

- ^ a b c 田村、根本『ビルマ』、208頁

- ^ a b 田村、根本『ビルマ』、212頁

- ^ 田村、根本『ビルマ』、210頁

- ^ 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、125頁

- ^ 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、124頁

- ^ 綾部、石井『もっと知りたいミャンマー』、124-125頁

参考文献[編集]

- 綾部恒雄、石井米雄編『もっと知りたいミャンマー』(弘文堂, 1994年12月)

- 太田常蔵「ナッ信仰」『アジア歴史事典』7巻収録(平凡社, 1961年)

- 大野徹、桐生稔、斎藤照子『ビルマ』(現代アジア出版会, 1975年10月)

- 高谷紀夫「ナッ信仰」『新版 東南アジアを知る事典』収録(平凡社, 2008年6月)

- 田村克己、根本敬『ビルマ』(暮らしがわかるアジア読本, 河出書房新社, 1997年2月)

- 田村克己、松田正彦『ミャンマーを知るための60章』(エリア・スタディーズ, 明石書店, 2013年10月)

外部リンク[編集]

- 中村羊一郎「ミャンマーのナッ信仰とナッカドー : タウンビョンとヤタナグの祭りを通して」『静岡産業大学情報学部研究紀要』第17号、静岡産業大学情報学部、2015年、 1-32頁、 NAID 110010047351。

- 市岡聡「ミャンマーの仏教遺跡訪問記 : バガンで見た信仰」『人間文化研究所年報』第12号、名古屋市立大学人間文化研究所、2017年3月、 57-63頁、 ISSN 1881-2686、 NAID 120006682911。

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%8A%E3%83%83%E4%BF%A1%E4%BB%B0

..

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét

Khi sử dụng tiếng Việt, bạn cần viết tiếng Việt có dấu, ngôn từ dung dị mà lại không dung tục. Có thể đồng ý hay không đồng ý, nhưng hãy đưa chứng lí và cảm tưởng thực sự của bạn.

LƯU Ý: Blog đặt ở chế độ mở, không kiểm duyệt bình luận. Nếu nhỡ tay, cũng có thể tự xóa để viết lại. Nhưng những bình luận cảm tính, lạc đề, trái thuần phong mĩ tục, thì sẽ bị loại khỏi blog và ghi nhớ spam ở cuối trang.

Ghi chú (tháng 11/2016): Từ tháng 6 đến tháng 11/2016, hàng ngày có rất nhiều comment rác quảng cáo (bán hàng, rao vặt). Nên từ ngày 09/11/2016, có lúc blog sẽ đặt chế độ kiểm duyệt, để tự động loại bỏ rác.