Dưới đó thì là bài nguyên của Liam.

---

2. Bài của Khôi

Cô giáo anh dạy rằng... “When I was learning classical Chinese, one of my teachers repeated grammatical rules to me over and over like mantras. By far the mantra which I heard the most was the following: “Unless a new subject is introduced, the subject remains the same.” (Trong ngữ pháp chữ Hán, nếu chủ ngữ mới không xuất hiện thì chủ ngữ của câu trước vẫn là chủ ngữ của phần kế tiếp) Và anh áp dụng lời dạy đó để phân tích “Bình Ngô đại cáo” như sau: Let us now look for the subject, or subjects, in the opening passage of the “Bình Ngô đại cáo.” 仁義之舉要在安民,吊伐之師莫先去暴。 惟我大越之國,實為文獻之邦。 山川之封域既殊,南北之風俗亦異。 自趙丁李陳之肇造我國,與漢唐宋元而各帝一方。 Nhân nghĩa chi cử, yếu tại an dân, Điếu phạt chi sư mạc tiên khử bạo. Duy, ngã Đại Việt chi quốc, Thực vi văn hiến chi bang. Sơn xuyên chi phong vực ký thù, Nam bắc chi phong tục diệc dị. Tự Triệu, Đinh, Lý, Trần chi triệu tạo ngã quốc, Dữ Hán, Đường, Tống, Nguyên nhi các đế nhất phương. “Benevolent deeds are those which focus on making the people peaceful. Troops sent to punish [rebels] take as their first aim the elimination of hostilities. Our kingdom of Dai Viet is truly a domain of civility. Just as the areas of its territory are distinct, so are the customs in the north and south also different. With the establishment of our kingdom by the Trieu, Dinh, Ly and Tran, together with the Han, Tang, Song and Yuan [we] have each empired over a region.” (Khôi comment: 而各帝一方 = nhi các đế nhất phương = mỗi bên xưng Đế một phương, mà anh dịch thành “have each empired over a region” thì quá kém. Anh không hiểu từ “Đế” trong bối cảnh văn hóa - chính trị của nó) Anh phân tích: For the sentence “Just as the areas of its territory are distinct, so are the customs in the north and south also different,” the subject is still “Our kingdom of Dai Viet.” “North” here cannot possibly refer to China, because no new subject has been introduced. (Đối với câu “núi sông bờ cõi đã chia, phong tục bắc nam cũng khác” thì chủ ngữ vẫn là “Đại Việt”. Từ “Bắc” ở đây không thể biểu chỉ Trung Quốc, bởi vì câu không có subject mới) 2) Bây giờ mời anh đọc chơi vài câu: 故人西辭黃鶴樓, 煙花三月下陽州。 孤帆遠影碧空盡, 惟見長江天際流。 Câu cuối, ai là subject của hành vi “thấy Trường Giang chảy miết bên trời”? Không có subject mới. Vậy subject của hành vi này “cô phàm” hay “yên hoa”? Đương nhiên không ai hiểu thế cả. Subject ở đây là Lý Bạch. Nếu chấp nhận kiểu phân tích diễn ngôn của anh thì đành chê Lý Bạch kém chữ Hán. Thêm bài nữa anh nhé. 風急天高猿嘯哀, 渚清沙白鳥飛回。 無邊落木蕭蕭下, 不盡長江滾滾來。 萬里悲秋常作客, 百年多病獨登臺。 艱難苦恨繁霜鬢, 潦倒新停濁酒杯。 Bốn câu đầu thì subject rõ rồi. Nhưng 4 câu cuối. Không có subject mới, vậy chẳng lẽ chủ thể của hành vi “làm khách xứ người” “lắm bệnh”, “lên đài cao một mình”, “tóc mai dày nhuốm màu sương gió” “thân già ốm yếu”… ở đây là… “trường giang”? Không ai hiểu thế cả. Người Hán đọc nó đều hiểu đó là Đỗ Phủ. Nếu chấp nhận kiểu phân tích diễn ngôn của anh thì đành chê thêm Đỗ Phủ kém chữ Hán, hoặc người Hán dốt ngữ pháp của thứ tiếng Hán mà cô giáo anh dạy ở trường đại học Mỹ. 3) Có lẽ vì dạy cho anh ở giai đoạn nhập môn, cô giáo anh trình bày về tiếng Hán theo cách những chàng trai Mỹ quen với mô hình ngữ pháp tiếng Anh có thể tiếp thụ được. Em nghĩ là cô giáo anh mong muốn sinh viên của mình khi đã thành giáo sư của University of Hawaii at Manoa thì phải hiểu rằng ngữ pháp chữ Hán phức tạp hơn thế nhiều lần. Đó là cấu trúc topic – comment structure. Khi biểu đạt bằng Hán ngữ, first, you give a topic, then you comment on it. Đó không phải là cấu trúc subject – verb - object như anh nghĩ. Anh không thể áp dụng cấu trúc subject – object của tiếng Anh để phân tích Hán văn được. Anh có thể đọc về topic – comment structure của Hán ngữ ở đây http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/Y02-1036 4) Topic – comment structure của “Bình Ngô đại cáo” Không chỉ các câu, mà cả các đoạn của tác phẩm này cũng được viết theo cấu trúc “topic – comment”. Vì không hiểu Topic – comment structure của “Bình Ngô đại cáo” nên anh phân tích nó rất linh tinh. Đoạn đầu, nó nêu topic là “Đại Việt”, sau đó comment về Đại Việt như sau: - Có nền văn hiến - Có biên giới lãnh thổ riêng - Có phong tục riêng - Có lịch sử, lịch sử này song song chứ không phụ thuộc vào China. - Có nhân tài để bảo vệ nó - Những nhân tài này đã nhiều lần đánh bại China Và đối với cả tác phẩm, thì cả đoạn mở đầu này cũng có tính chất của một topic, những phần còn lại cũng mang tính chất của một comment. Đặt hai chữ “bắc – nam” trong ngữ cảnh “topic – comment” ấy thì chẳng thể có cách hiểu nào khác, rằng “bắc” là China còn “nam” là Đại Việt. 5) Phân tích một khái niệm, mà không đặt nó vào trong context của cả văn bản, lại đặt nó vào context của lời cô giáo dạy tiếng Hán cho mình thời sinh viên. Sao lại làm thế được hả anh? Thế rồi anh chém tiếp: nếu “bắc” không phải là China thì là cái gì? E hèm, để tớ xem nào, Lê Lợi ở Thanh Hóa (nam) còn Thăng Long ở “bắc”. Chẹp, ý Bình Ngô đại cáo muốn nói hai vùng bên trong Đại Việt có phong tục khác nhau. Rồi vẫn mạch cảm hứng ấy mà chém tiếp là chữ “Ngô” không phải là China. Để chứng minh chữ Ngô này không phải là nhà Minh thì dựa vào… “Dư địa chí”. Your argument is so ridiculous, Lê Minh Khai. If your essay is my student’s one, it get zero :D

https://www.facebook.com/notes/nguyen-luong-hai-khoi/ph%C3%A2n-t%C3%ADch-ki%E1%BB%83u-ph%C3%A2n-t%C3%ADch-di%E1%BB%85n-ng%C3%B4n-c%E1%BB%A7a-anh-l%C3%AA-minh-khai/10153644862877027

1. Bài của Liam

North and South in the “Bình Ngô đại cáo”

The “Bình Ngô đại cáo” is today one of the most famous historical documents in Vietnam. Virtually everyone in Vietnam knows at least the opening passage of this fifteenth century text. However, the way in which it has been taught, and the way it is quoted over and over, is incorrect.

This document is attributed to the literatus, Nguyễn Trãi, who reportedly wrote this declaration on behalf of the new emperor, Lê Lợi, a man who founded a new dynasty in 1428 after driving out Ming troops which had occupied the area for over 20 years.

Today Vietnamese see this document as a “declaration of independence” which declares the distinctness of Vietnam. The main evidence for this view is a line which comes near the beginning of this document which mentions that the territory and the customs of the “north” and “south” are different.

Throughout much of the period prior to the twentieth century we can find the words “north” and “south” used by Vietnamese writers to refer to “China” and “Vietnam,” respectively. However, that is not what these terms refer to in the “Bình Ngô đại cáo.” The reason why I say this is because it is grammatically impossible for those two words to have that meaning in this text.

When I was learning classical Chinese, one of my teachers repeated grammatical rules to me over and over like mantras. By far the mantra which I heard the most was the following: “Unless a new subject is introduced, the subject remains the same.”

Let us now look for the subject, or subjects, in the opening passage of the “Bình Ngô đại cáo.”

仁義之舉要在安民,吊伐之師莫先去暴。

惟我大越之國,實為文獻之邦。

山川之封域既殊,南北之風俗亦異。

自趙丁李陳之肇造我國,與漢唐宋元而各帝一方。

“Benevolent deeds are those which focus on making the people peaceful.

Troops sent to punish [rebels] take as their first aim the elimination of hostilities.

Our kingdom of Dai Viet is truly a domain of civility.

Just as the areas of its territory are distinct, so are the customs in the north and south also different.

With the establishment of our kingdom by the Trieu, Dinh, Ly and Tran, together with the Han, Tang, Song and Yuan [we] have each empired over a region.”

I have placed in bold the terms which we can understand as the subjects of these sentences. For the sentence “Just as the areas of its territory are distinct, so are the customs in the north and south also different,” the subject is still “Our kingdom of Dai Viet.” “North” here cannot possibly refer to China, because no new subject has been introduced.

So if this sentence doesn’t refer to Vietnam and China, then what does it refer to? Well let’s see, Lê Lợi was from Thanh Hóa and had just brought the entire realm under his control, a realm in which scholars in the north (Hanoi) had recently cooperated with the Ming. With that as a clue, I’ll leave it to others to figure out the rest.

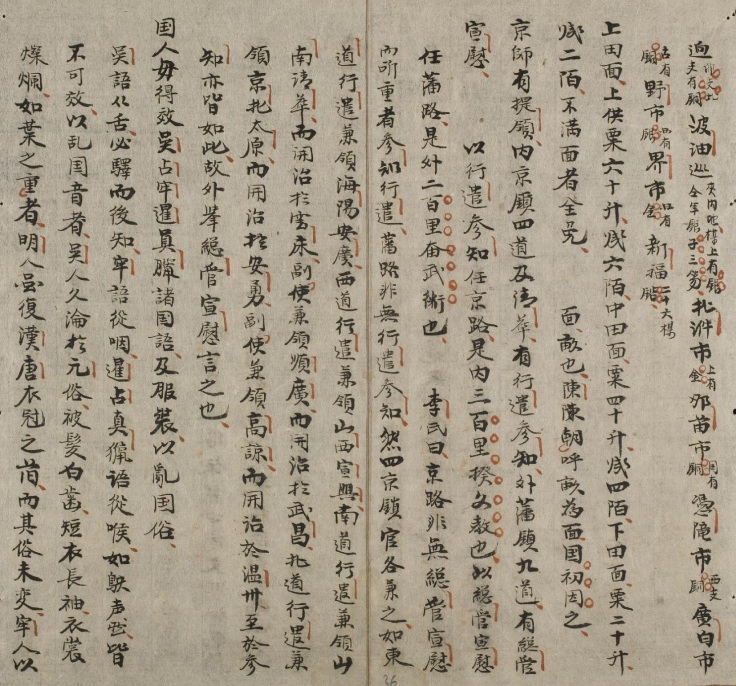

The image here is not from the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, where the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” was first published, but from the 1825 text, the Hoàng Việt văn tuyển. The version in this latter text adds two characters to the beginning of the text, 蓋聞, which can be roughly translated as “It has been heard that. . .” or “I have heard that. . .”

There is a fifteenth-century document that is today very famous in Vietnam. It is called the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” (The Great Proclamation on Pacifying the Ngô) and today it is seen in Vietnam as a kind of “declaration of independence” that was made after the Ming Dynasty forces were driven out of the Red River Delta after some two decades of occupation.

For years I have had problems with this interpretation of this document, and there are many posts on this blog which deal with this topic. I do not see this document as a “declaration of independence” but as a “declaration of victory” of one faction in the Việt world over another faction.

The faction that was victorious at that time was the group of people who had supported Lê Lợi, the man who drove out the Ming and established the Lê Dynasty. From the perspective of some of the elite in the Hanoi area (and perhaps in more coastal regions like Hải Dương), Lê Lợi was a kind of “country bumpkin,” and as such, they did not support him. Instead, they chose to collaborate with the Ming.

The “Bình Ngô đại cáo” makes this very clear, as it emphasizes how for many years Lê Lợi had to struggle more or less on his own against the Ming.

That is a very odd narrative for a “declaration of independence.” Shouldn’t a “declaration of independence” emphasize how “all of the people united together” to resist the foreign invader?

That is one point that is problematic about the current interpretation of this document. The other is that people today see the term “Ngô” in the title as indicating “the Ming.” But that is clearly not what this term referred to.

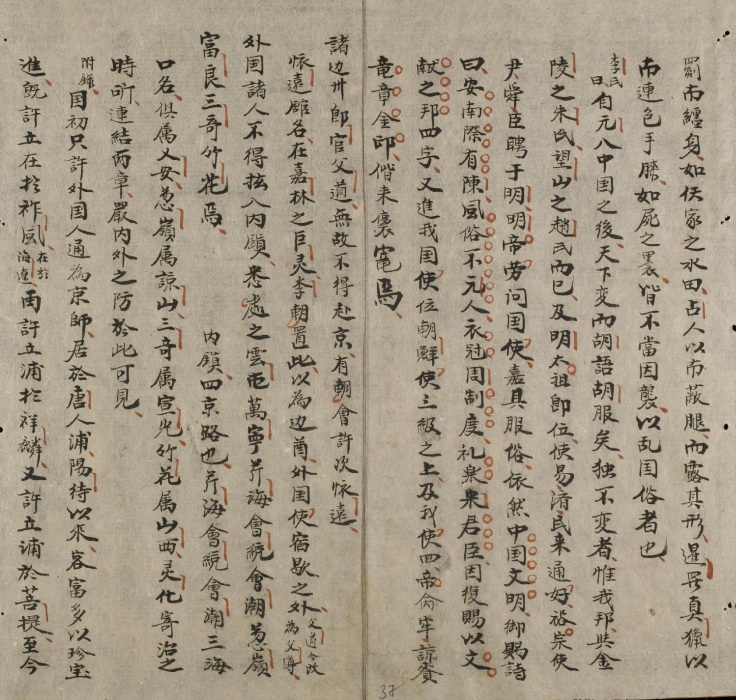

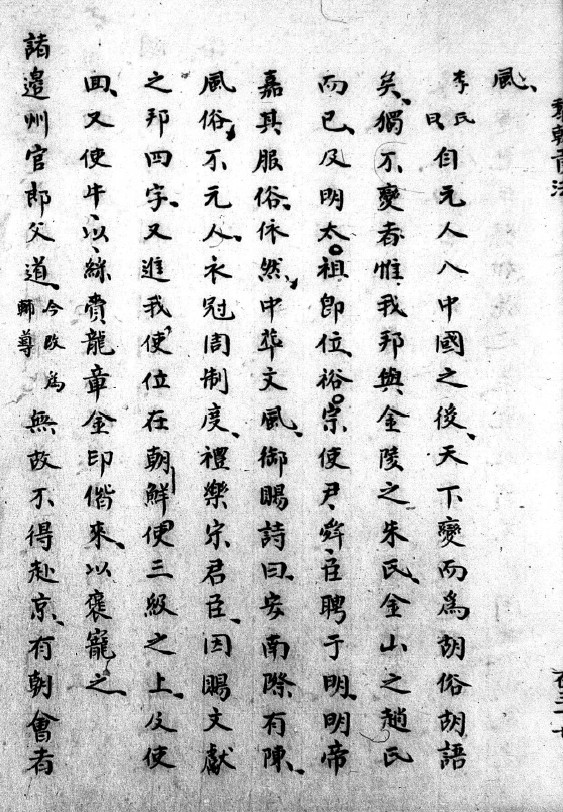

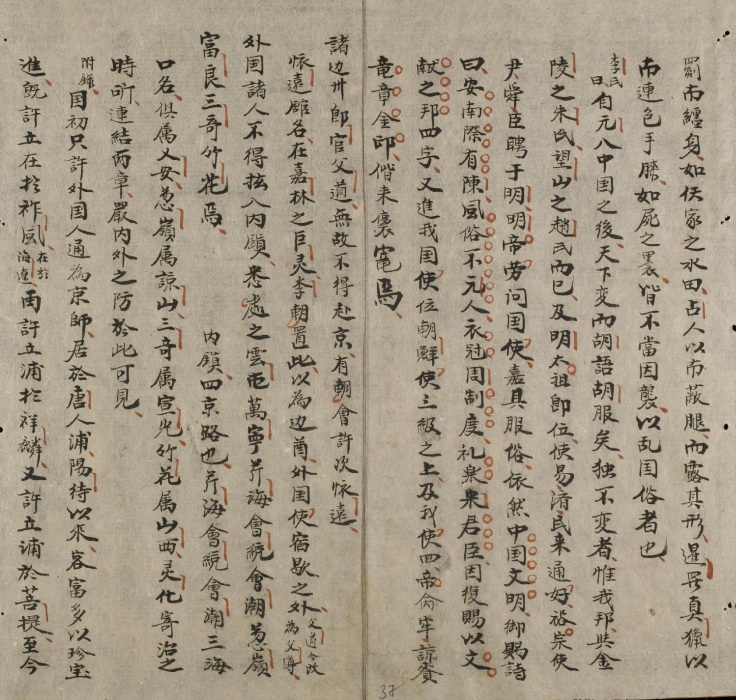

Clear evidence for this comes from a text that was produced by a scholar who supported Le Lợi, Nguyễn Trãi. That text is called the Dư địa chí (The Treatise on the Territory) and it contains a passage which states the following:

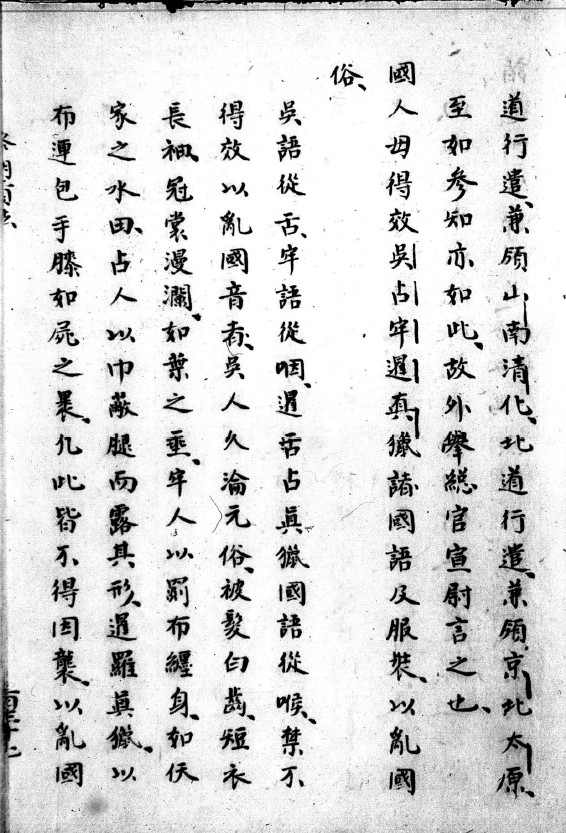

“The people of the kingdom should not follow/imitate the national languages or dress of the Ngô, Chiêm [i.e., Cham], Lao, Xiêm [i.e., the Siamese] and Chân Lạp [i.e., the Khmer] as this causes chaos for national customs.”

If we just read that one line, then it looks like Nguyễn Trãi must have used the term “Ngô” here to refer to “the Chinese.”

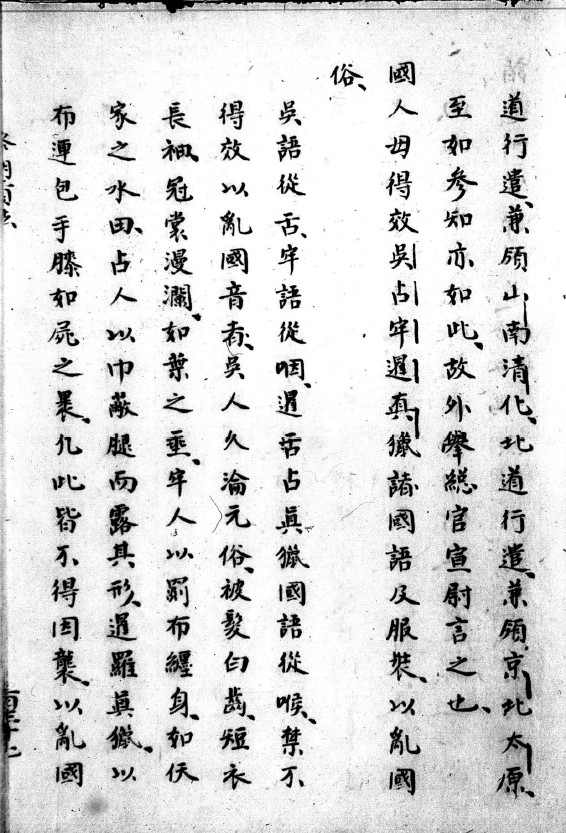

However, he goes on to explain that “The Ngô people have long fallen into following Yuan [meaning the Mongol Yuan Dynasty] customs. They let their hair down, have white teeth, wear short shirts with long sleeves, and caps and robes of variegated colors like layers of leaves.”

(Người Ngô lâu ngày nhiễm thói tục của người Nguyễn, tóc xõa, răng trắng, áo ngắn mà tay áo dài, mũ xiêm lòe loẹt, lớp lớp như lá. 吳人久淪元俗,被髮白齒,短衣長袖,冠裳燦爛,如葉之重者.)

That’s an odd statement to make about “Chinese,” isn’t it? After all, Chinese always had white teeth. It’s only the Việt who had teeth that were not white. So if “having white teeth” is a sign of having “long fallen into following Yuan customs,” then this statement clearly can’t be about “the Chinese.”

What is more, some versions of this text then state that “Although the Ming people have returned to wearing the caps and robes of the Han and Tang, their [meaning the Ngô] customs have still not changed.”

(明人雖復漢唐衣冠之舊而其俗未變. Người Minh tuy khôi phục áo mũ Hán Đường xưa, nhưng thói tục của họ [tức người Ngô] vẫn không đổi.

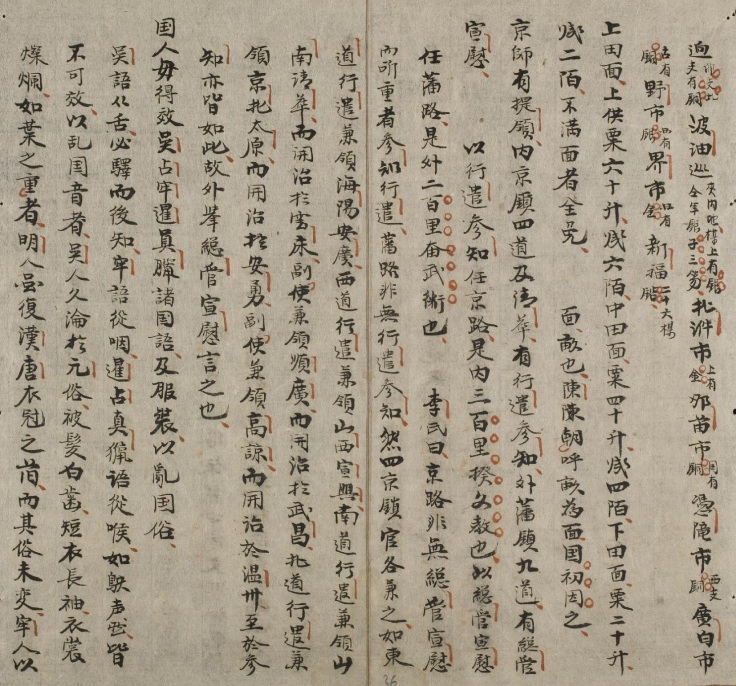

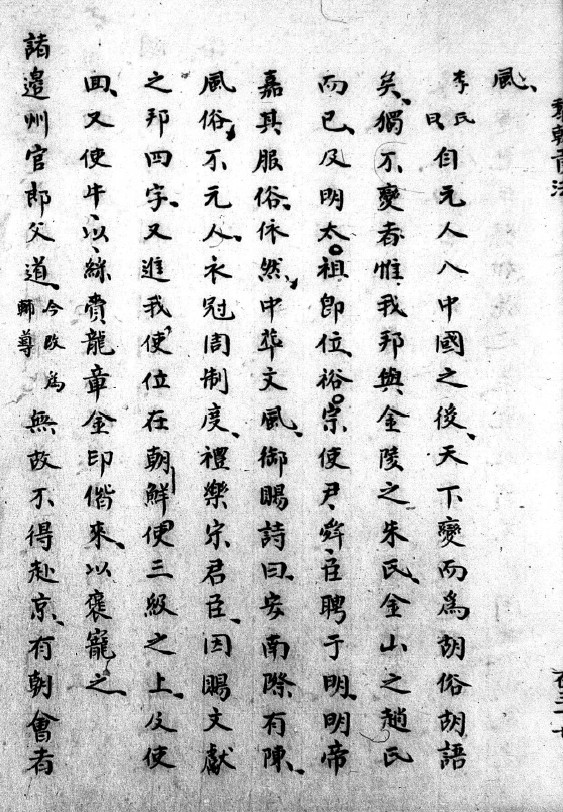

This passage in the Dư địa chí is followed by a comment by one of Nguyễn Trãi’s contemporaries, Lý Tử Tấn, which states that:

“After the Yuan people entered the Middle Kingdom, All Under Heaven was transformed and followed Hu [meaning “northern/nomadic barbarian”] customs and the Hu language. The only ones to not change were Our Domain and the Zhu clan from Jinling and the Zhao clan from Jin/Wangshan.”

The “Zhu clan from Jinling” is clearly a reference to the ruling family of the Ming Dynasty. As for the Zhao clan, that is also obviously a reference to the ruling family of the Song Dynasty, although different versions of this text identify the Zhao with different place names (Jinshan, Wangshan, etc.).

So according to Lý Tử Tấn, the Ming ruling family did not “fall into following Yuan customs.” So the Ming ruling family was clearly not the Ngô. And according to Nguyễn Trãi “Ming people” went back to wearing the caps and robes of the Han and Tang, so the “Ming people” were clearly not the Ming ruling family as according to this account, the Ming ruling family never changed the way they dressed.

Nor did the Việt ruling elite change the way they dressed, for Lý Tử Tấn notes that when the Ming Dynasty came to power, the Trần Dynasty sent envoys to the Ming, and they were praised for the fact that they still dressed in old-style (i.e., Song style) robes.

So the Ming ruling family was not the Ngô, and the people the Ming ruled over were not the Ngô either. What is more this text indicates that Nguyễn Trãi and Lý Tử Tấn agreed with the practices of the Ming and its people, while they clearly did not like the cultural practices of the Ngô.

So who were the Ngô?!!

Again, I think John Whitmore is right in thinking that the Ngô were members of the coastal “Chinese” community in Đại Việt, and that these people had collaborated with the invading Ming forces, and that as a “local power” they had the potential of challenging Lê Lợi’s legitimacy after the Ming left.

They were thus a group that Nguyễn Trãi needed to “declare pacification” over in the “Bình Ngô đại cáo.”

In other words, as I’ve always argued, this document was saying that “we are in charge now, and you will follow our orders.”

What else can the Dư địa chí tell us about the Ngô? We can speculate that the Ngô were a group of people who probably had ties with the Chinese world through trade, but who were probably not as scholarly as someone like Nguyễn Trãi, and that therefore they didn’t think much about having to dress in a certain way.

Perhaps some of these people were “Chinese” who upon arriving in Đại Việt they had originally “gone native” and died their teeth black and tied their hair up like the Vietnamese elite, but in the years before the Ming came to power, they had “fallen into following the customs of the Yuan” and had let their hair down and had stopped dying their teeth, as well as changed the way they dressed.

Or perhaps this was a “hybrid” community of Chinese and Vietnamese, some of whom had intermarried, and perhaps it was the Vietnamese among this community whom Nguyễn Trãi was criticizing for having changed their ways and were no longer blackening their teeth and tying up their hair.

This is speculation, but the one point that the Dư địa chí makes perfectly clear, is that “the Ngô” were not “the Ming.” This term referred to someone else. And as I’ve always argued, I think it refers to a local group – the people who did not support Lê Lơi so that he had to struggle against the Ming on his own, a point that, again, the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” clearly emphasizes.

https://leminhkhai.wordpress.com/2016/08/02/the-ngo-in-the-du-dia-chi-were-not-the-ming/

Đồng í với NLHK, LMK không thể căn cứ trên cấu trúc ngữ pháp của BNĐC để kết luận Ngô không phải Minh.

Trả lờiXóaRất tiếc NLHK, dù phản bác LMK một cách châm biếm (rất không nên), không đưa ra luận giải nào của riêng mình.

Tôi cũng ngạc nhiên, một người nghiên cứu (là GV đại học) như NLHK, lại ngạc nhiên (cũng một cách châm biếm) trước việc LMK dùng DĐC (cũng của NT) để luận giải về Ngô trong BNĐC. Có gì sai ở đây đâu.

Một đề tài thiệt hay, nhưng vì không có chuyên môn nên tôi chỉ lớt phớt vậy thôi. LMK đang chuẩn bị một loạt bài, nghe nói là "ở mức chi tiết", về đề tài này. Thử chờ xem.

Cuối cùng là hehe English của NLHK, vừa không đúng chỗ, vừa sai, vừa lại... châm biếm rất không nên:

Your argument is so ridiculous, Lê Minh Khai.

If your essay is my student’s one, it get zero :D

Ít nhất, trên đời không có "it get". Học sinh tiếng Anh lớp 6 cũng biết, ở thì hiện tại đơn, ngôi thứ 3 số ít, động từ phải thêm "s" [it gets]. Đấy là điều sơ đẳng, không đáng bàn.

"Tinh tế" hơn một chút, "my student" là không xác định. Vì "sinh viên tôi" là sinh viên nào trong số hàng trăm sinh viên (có thể có) của NLHK?

Cuối cùng, trừ khi LMK là học trò của NLHK, câu trên thuộc loại câu "điều kiện không thực" (unreal conditional sentences). Một câu loại này, động từ ở "if-clause" buộc phải ở quá khứ đơn, mệnh đề kia thêm "would" trước động từ [if you were one of my students, your essay would get a zero]. Một lỗi sơ đẳng của, có lẽ, học sinh học tiếng Anh lớp 8.

Bây giờ mới đọc lời phê của thầy hehe cho em NLHK. Quả thật em này giỡn chơi kiểu này, như thầy hehe đã chỉ ra, là thiếu nghiêm túc trong vấn đề học thuật (bên kia Liam thì đặt vấn đề và triển khai nghiêm túc, chuyện đúng sai để soi sau).

XóaÔng em Nguyễn Lương Hải Khôi là lưu học sinh ở Nhật Bản, không chuyên tiếng Anh, nên thầy hehe chỉ ra thế thì quả là đúng rồi !

Đang chờ Liam triển khai tiếp vấn đề bác hehe à.